🌡️ Heritage breeds: the future of climate-proof cows

Welcome back to The Regeneration Weekly, a newsletter delivering regenerative food and agriculture news to your inbox every Friday. Not a subscriber yet?

Before diving into today’s topic, I would like to let our readers know that this will be my last post as the author of The Regeneration Weekly.

I would like to thank Soilworks for the opportunity to launch and write 40 editions of this newsletter with the sole mission of accelerating consumer awareness of regenerative agriculture. I'm equally grateful for each and every reader who cared enough about our food system to subscribe in the first place.

To stay in the loop about my future thoughts on regenerative technologies, circular systems, and environmental ethics, please submit your contact information here. And if you want to stay connected, you can find me on LinkedIn.

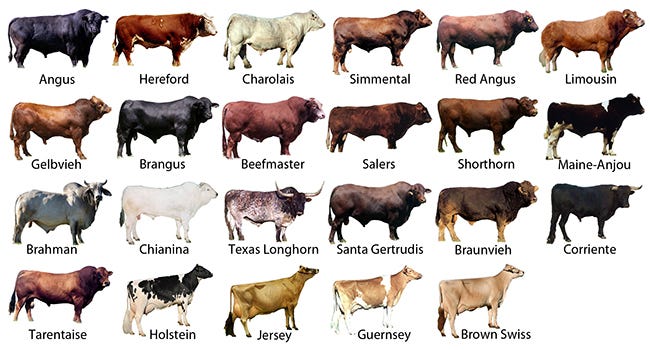

Progress: Before industrial animal agriculture was ubiquitous, our forefathers depended on “heritage” breeds of livestock for three purposes: meat, milk, and draft power. These cows, many of which are indigenous, were selected to develop unique traits tailored to local conditions. In contrast to today’s cows, which are pumped full of commodity crops and antibiotics in large indoor feeding facilities, these breeds of a bygone era thrive in pasture-based settings. But similar to many other traditional breeds that do not thrive in factory farm settings, they are in literal danger of going extinct. As it stands, close to 17 percent of the world’s livestock breeds face extinction. And only 14 breeds provide 90 percent of our animal products in the worldwide food supply. In the US, less than 4,000 Guernsey cattle were registered last year, down from the 44,000 in 1930; the number of Red Poll cows has fallen from 6,000 in the 1920s to just 524, and only 245 Milking Shorthorns exist when several thousand were tallied in the 1970s.

Since the rise of industrial agriculture, regional cattle breeds have been supplanted by a handful of commercial breeds designed to gain weight faster, consume feed more efficiently, mature sooner, and withstand confinement - all while producing a larger volume of meat or milk. In 1950, for instance, the average dairy cow produced about 5,300 pounds of milk a year. Today, the black-and-white Holstein can produce 23,000 pounds of milk per year. And of the roughly 9 million dairy cows occupying the nation’s rural landscape, about 94 percent are the Holsteins - 99 percent of which can be traced back to the semen of two bulls from the 1960s. For many, this consolidation and intensification of animal production seem necessary when considering the fact that the demand for animal-based products is expected to more than double by 2030. In reality, issues crop up when breeding programs focus on maximizing output at the expense of everything else.

Industrial breeds rely on artificial insemination and often select for bloodlines with the highest production potential. But basic biology teaches us that inbreeding, which isn’t much better than shrinking biodiversity, increases the risk of inherited disorders and infertility while also reducing the ability of a population to evolve in the face of a changing environment. This may explain why, in the summer, even after being cooled with fans and sprinklers, Holsteins in Florida typically drop 10 to 15 percent in milk production. Heat, in particular, affects cattle in subtle ways, none of them good. When the air gets too hot and humid, the cows’ immune systems falter - decreasing their appetite and making them more vulnerable to parasites. Moreover, hot temperatures can lead to Holsteins’ fertility plunging by 20 to 25 percent, which increases greenhouse gas emissions generated by livestock. And new research reveals that improving the fertility of cows can lead to a 24 percent reduction in global methane emissions.

Thus, as the world’s appetite for meat continues to swell and environmental changes (i.e., disease, famine, drought, and land degradation) endanger global food security, ranchers and scientists alike must start to identify “climate-proof” cows that can thrive in warmer climates. Luckily, heritage lines have been carefully bred over generations - making them more resistant to disease and environmental volatility than their industrial counterparts. Several types of indigenous animals have a genetic component that allows their bodies to run 1 to 2 degrees cooler than other breeds. The Pineywood cow, for example, is a heat-tolerant breed adapted to the US Southeast after traveling to the US with the Spaniards in the 1500s. Moreover, the Raramuri Criollo cow, which means "light footed one," is another traditional breed being tested as a replacement for Angus and Hereford beef cattle in the US Southwest. And the South Poll is quickly rising in popularity because of its shorter, sleeker hair coat, known as “slick,” which helps in regulating body temperature. With this in mind, heritage breeds may actually act as a modern insurance policy against the type of collapse seen during the Irish Potato Famine.

In short, genetic diversity is a prerequisite for adaptation in the face of future challenges. If a new disease were to pop up tomorrow, massive swaths of the commercial cow population could be susceptible since so many of them possess the same genes. Yet, increasing our stocks of indigenous cows, which possess genetics that could ultimately divert a food crisis if industrial-bred cows do not respond well to global warming, can identify climate-smart cattle for a future food system. These resilient animals could also help reorient how selective breeding is conducted through more natural criteria. By cross-breeding heritage lines with other breeds, ranchers can also adapt their existing cattle to do better on a grass diet, in addition to improving their adaptability to new environments. In doing so, we can usher in a cost-effective and ethical way to insulate the beef and dairy sectors from the effects of global warming.

As it stands, the biggest hurdle to making change is convincing dairy farmers and ranchers to prioritize breeding cows for climate resiliency, which is not yet correlated to any direct financial benefit like milk production or size. Conceivably, there are ways around this. The European Union, for example, subsidizes heritage-cattle husbandry as part of an effort to protect Europe’s cultural history. And while genetic sources have historically been a behind-the-scenes layer in food production, completely removed from consumers, a more lucrative approach for farmers could be a marketing push similar to the campaign of the heirloom tomato - tapping into the farm-to-table ethos that has dominated specialty grocery stores. In fact, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) already started providing grants to local farmers to better market heritage breed livestock products. Similar to the way that companies have started advertising their food production practices (i.e., grass-fed or antibiotic-free), genetics may be the next branding trend - generating higher margins for sustainable producers and higher value for eco-friendly customers.

Listen: On this episode of The Doctor’s Farmacy, Mark Hyman sits down to talk to Fred Provenza, the professor emeritus of Behavioral Ecology in the Department of Wildland Resources at Utah State University, about the mystical world of phytochemicals and what they can do for humans and animal health. It is well known that eating a diverse variety of phytonutrients is a powerful tool to support optimal health. Another important aspect of phytonutrients is the impact they have on making animals healthier, too; grass-fed livestock who graze on high-quality pasture, with lots of different kinds of wild plants, digest a vast array of phytonutrients. In doing so, the animals can provide much healthier meat that passes more nutritional benefits along to eco-friendly consumers.

Shop: Maryiza by Forested Foods is a line of single-origin honeys from the indigenous trees of Ethiopia's biodiverse-rich Southwestern Afromontane Region. Forested Foods is a female-founded and led agroforestry enterprise. To date, they have trained and worked with almost 200 smallholder farmers and their families to regeneratively produce and bring the most distinct forest products - starting with honey - to market. Their vision is to build a world where forests are more lucrative conserved vs destroyed, by unlocking more commercial value from forests for all. Follow their journey as they build a new value proposition for forest conservation and access the rich flavors of raw, biodynamic honeys from Geteme, Bissana, Grawa, and Abalo tree flowers. The Regeneration Weekly readers can use the code “SOILWORKS” at checkout to receive a special discount (15% off orders valued at $30+).

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features - we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.

The Regeneration is brought to you by Wholesome Meats | Soilworks | PastureMap.