Biodiversity loss & climate crises: two sides of the same coin

Climate change changes habitats, intensifying the effects of climate change, leading to biodiversity loss across many ecosystems. To tackle one challenge, we must tackle both.

Climate change significantly impacts the survival rate of plant and animal species. Our changing climate and resulting weather extremes make many species’ natural habitats hostile or uninhabitable, causing biodiversity loss and accelerating our rate of climate change.

Why is biodiversity important to ecosystems and our future?

Different species fulfill important roles in every ecosystem. In ecosystems that have a variety of species that can do any given function, the ecosystem is more resilient - it’s able to respond to disturbances like disease or fire without totally collapsing. What looks like redundancy is insurance.

Ecosystems with limited diversity, including monocultures, are more prone to disease and other disasters than natural ones.

For too long ecosystems have been treated like machines that will continue to work so long as basic conditions are met. For example, if we deem one species as undesirable, we remove that species and replace it with commercially valuable species that can be harvested at constant, more predictable rates. Yet this ignores the complexity of nature and the importance of biodiversity, resulting in catastrophic consequences.

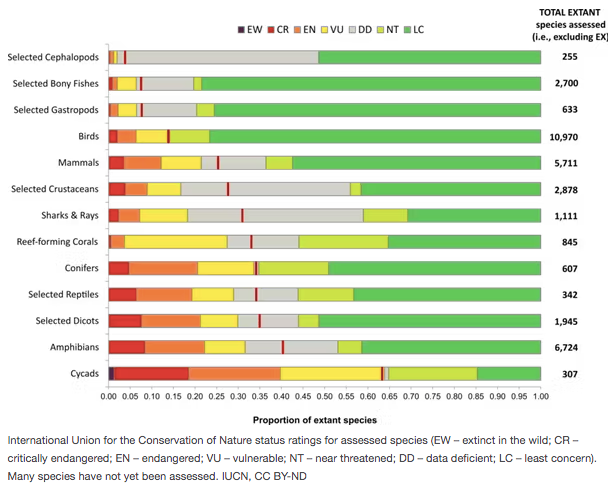

We degrade our biodiversity through urbanization, pollution, deforestation, etc., and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating.

“With biodiversity loss, we not only lose nature, but we also lose some of our best defenses against climate change,’ said Myron Peck, who leads the Department of Coastal Systems at the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ).

“Our oceans, forests, peat bogs, and wetlands all act as natural carbon sinks, absorbing harmful carbon from the atmosphere.”

To tackle climate change, we must also tackle biodiversity loss.

We see this relationship firsthand with our work in regenerative agriculture. Soils that support diverse ecosystems, as Andy Hector recently reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, can “generate soils that are richer in plant nutrients and more productive in plant biomass and that store more carbon.”

The more carbon we can capture and store in the soil, the more the Earth can regulate GHG levels in the atmosphere, leading to a more stable climate.

Why does biodiversity matter to people?

Biodiversity is the backbone of the continued existence of our species and planet. Remove the backbone, and everything crumbles - our climate, food systems, weather, economies, communities, and ways of life.

Humans depend on the functions performed by diverse ecosystems. They produce oxygen, purify and detoxify the air and water, store and cycle fresh water, form topsoil, prevent erosion, regulate the climate, and produce raw materials, foods, and medicines.

Technology can’t outcompete nature because technology depends on nature.

Some economic and social arguments further illustrate the importance of biodiversity:

The value of the world’s ecosystem services has been (conservatively) estimated at $33 trillion per year.

The state of New York discovered that wetlands and other natural systems in the watershed accomplished water purification and filtration that would require an $8 billion water treatment plant to replace. Protecting and remediating these natural systems cost much less.

Over 75% of staple food crops and 90% of flowering plants worldwide depend on pollination by insects and other animals. Between 100,000 and 200,000 species of animals act as pollinators, and their populations are declining.

Crop diversity is substantially falling as agri-business is taking over food production from small family operations that once supplied our population. The practice of saving seeds is being abandoned in favor of hybrid varieties that require reseeding every year and large quantities of chemicals decreasing the self-sufficiency of farmers worldwide and reducing the genetic diversity of food crops making them more susceptible to disease and pest outbreaks.

Virtually all natural and pharmaceutical medicines are composed of (or derived from) natural compounds of plants, fungi, microbes, and animals. In areas of severe environmental degradation, many species with known or even unknown healing properties are threatened by extinction.

The highly biodiverse coastal environment of British Columbia contributes 7-8% to the provincial GDP.

Plants, animals, and people have value in and of themselves, and preserving biodiversity not only mitigates climate change but is also an important investment in our future.

Regenerative agriculture can build biodiversity

Regenerative practices not only increase the health of our soil and land, but also attract more biodiversity, build climate resilience, manage our GHG levels, and slow the rate of climate change.

More corporations today are recognizing the impact of regenerative agriculture for their carbon drawdown capabilities, and, in turn, financially supporting farmers to adopt such practices, and over 100 countries have laws or policies in place that require or enable the use of biodiversity offsets.

If we continue to encourage and support the transition to regenerative agriculture, we can indeed tackle climate change and biodiversity loss simultaneously.

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features - we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.

If you have any products you would like to see featured, please respond to this newsletter or send an email to meg(at)soil.works

The Regeneration is brought to you by Soilworks | Wholesome Meats | Cream Co. Meats | Grassroots Carbon | Grazing Lands | RangeWard

to my opinion it is dangerous and counterproductive to set a value for the world's ecosystem services. It is a door open to make them marketable. For instance, I can buy ground water in a particular region for a certain price, and then compensate by financing tree plantations in another region. This means: including nature into a highly imperfect economic system, that eventually will lead to a privatisation of commons. Whereas any economic system is instead included in nature (Geneviève Azam). Viewed from 'nature' – a different perspective – it is doubtful that human activity would be worth as much as 35% (1/2.8) of 'everything', as the activity of only one species amidst tens of thousands of other species.

I strongly encourage everyone to read Nature’s Best Hope by Douglas W. Tallamy for an excellent examination of the urgency and importance of the biodiversity crisis.