Do we have the land for regenerative grazing?

And if so, could we meet our current beef demands with only regeneratively-raised beef?

I’m frequently asked to explain not only how our current system is broken, but also how regenerative grazing is a better solution than many recent tech or lab-based “solutions.”

I often hear, “Do we have enough land for all grass-fed, regeneratively raised beef?”

First, and often overlooked when discussing this topic with folks who are long detached from how food is produced: all beef cattle spend most of their lives on pasture and are either finished on feedlots or on grass. An “all grass” beef supply wouldn’t displace us from our homes nor have much of a noticeable effect on our grazing lands when we drive through the countryside. The agricultural lands already exist - it’s how we use them that would change.

Second, it’s important to remember that an industrial monocropping system has drastically different impacts on our land than regenerative agriculture. It does take more land to produce regenerative, grass-finished beef, but in this scenario, we don’t quantify the other benefits and marketable products from well-managed grazing lands.

But how much more, and most importantly: do we have enough land to scale regenerative grazing to meet current demands?

If we look at the current levels of underutilized pasture, idle grassland, and cropland that could be regenerated in an all-grass scenario, the short answer is yes.

Here’s how:

Finishing moderate-framed cattle requires bringing them from 800 pounds to 1,200 pounds. Assuming a weight gain of about two pounds per day, it’ll take about 200 days for cattle to get to slaughter weight.

If the cattle weigh, on average, 1,000 pounds during their finishing phase and each animal needs to consume about 3.2% of forage dry matter (DM) of body weight per day to achieve their desired weight gain, each animal would consume about 32 pounds of DM, or 6,400 pounds of forage DM, or roughly 3 tons, during their finishing phase.

Healthy soils will produce anywhere from three to eight tons of forage DM per acre, meaning that it would take an acre or less annually to grass finish a beef steer.

Why do these numbers matter? We still don’t know if we have enough land to support an all-grass finished beef production…yet.

For simplicity, let’s assume the average grain-fed beef production in the U.S. is 30 million head per year (it’s actually been hovering around 26-29 million, but who doesn’t like an added challenge?).

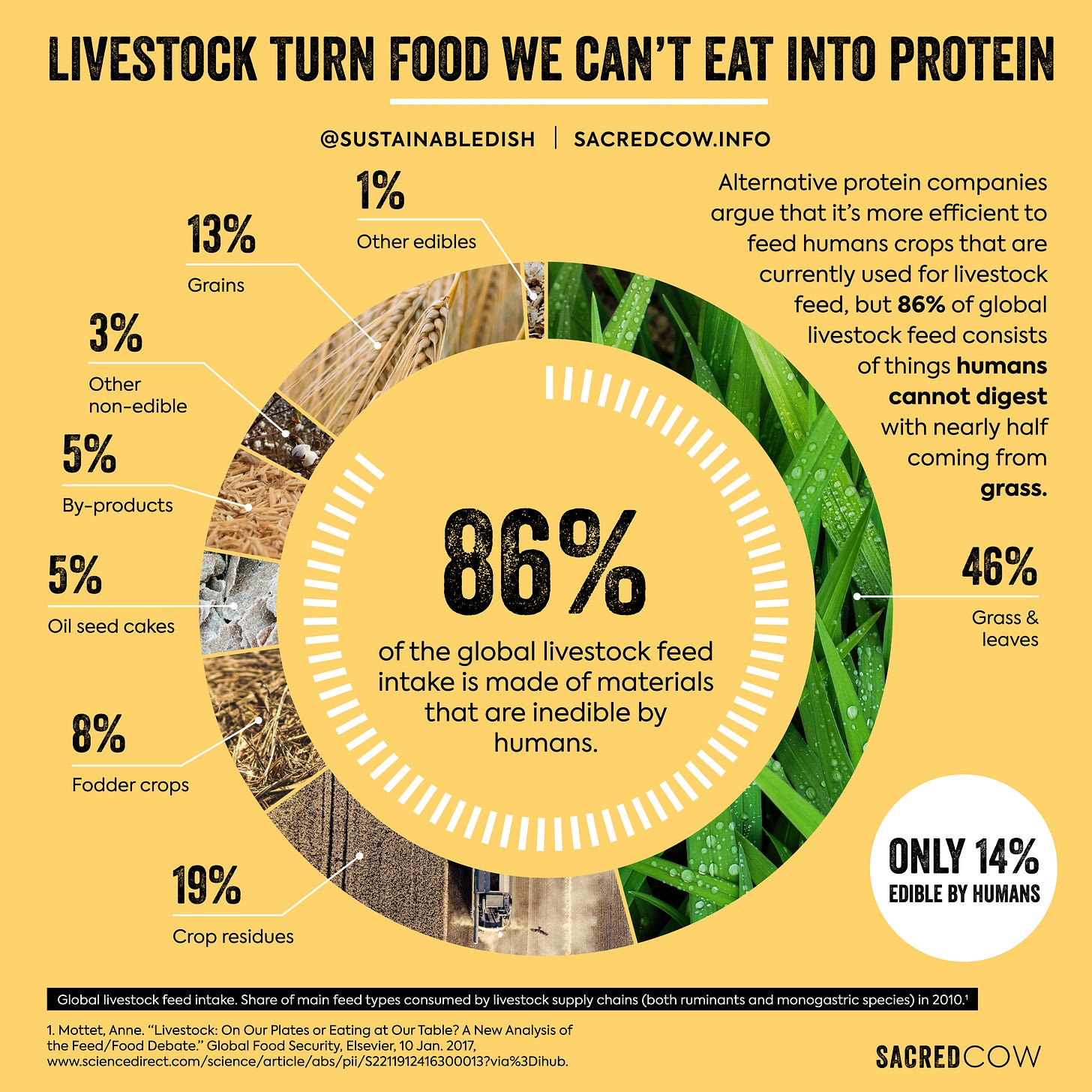

If we are now finishing cows only on grass, we can reduce the 90-94 million acres of corn. About 30-40% of our corn production is used for livestock feed (for cattle, but largely for pigs and chickens), with the remainder used mainly for high-fructose corn syrup and ethanol. Brief side note: cattle consume dried distiller’s grains, a by-product of alcohol that no one else would eat, which is included in this percentage allocated to “livestock.” The point is that converting these crops would not threaten food security (or at least it wouldn’t threaten our nutritious food security).

If we take only 15 million acres of these cornfields, each of them could finish an understated 15 million cattle (a cautious one steer per acre, where many experts estimate converted cornfields could finish nearly two steers per acre).

Add in the 3.5 million acres of other grain-producing acres (soy, wheat, and other small grains) that we no longer need for crops, and we’re up to 18.5 million acres, or 18.5 million cattle.

Now let’s consider the 500,000+ million acres of privately held pastureland in the US. With only about 30% being utilized to capacity, we’d have even more opportunities for better grazing animals. Let’s assume that we use just 10% (50 million acres) of this land and conservatively assume it can only produce 10 million cattle, we’re now up to 28.5 million grass-finished cattle.

Throw in just 30% of the current 22 million acres of land in the Conservation Reserve Program, a program that notoriously pays farmers to allow the land to sit idle, and we have an additional 6.6 million acres that, despite its degradation, could produce another conservative 4.4 million head of cattle.

This brings us to a grand total of 32.9 million cattle finished on grass, which is more than the current beef herd finished in feedlots.

We’re already over our current production numbers and haven’t yet considered the 12 million acres of irrigated Intermountain Region of the United States, which we’ll estimate can produce a conservative 1.67 head per acre. If we only use 30% of those acres, we’ll produce an additional 6 million cattle per year.

That’s a highly conservative 38.9 million beef cattle (many experts estimate our lands can grass finish between 40-50+ million cattle).

It’s important to note that these calculations are also based on current practices. We’re still learning how to optimize soil health, stocking rates, and genetics for grass-finishing. Data from Michigan State University reported a 30% increase in the overall productivity of converting to regenerative grazing.

So, do we have enough land to finish all cattle on grass? The math seems clear that we do.

Will we? Probably not anytime soon.

We have an entire monocrop industry dependent on cattle to upcycle their waste into bioavailable protein.

Different regions also have area-specific ecosystems that might be better suited for different food.

The bottom line is that if someone’s main argument against regenerative beef is its lack of scalability, they’re hoodwinked.

We are not deficient in grazing acres, and the longer we argue whether or not we have the capacity for grass finishing our beef supply, the longer we ignore bigger issues, such as:

More than 80% of all grass-fed beef currently sold to consumers in the U.S. under a USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) “Grass-Fed” label is actually imported grass-fed beef labeled “Product of USA”.

Feedlot style “grass-fed” beef, meaning beef that was finished in a feedlot that was fed a “Total Mixed Ration” that is “technically” a forage-based feed, but far from the Old MacDonald’s visual we relate to grass-fed beef.

No trusted certification for grass-fed, grass-finished, regenerative beef

Deficit of producers who are highly skilled at uniform, consistent grass finishing, especially year-round.

No national consumer brand awareness, exacerbating consumer confusion and distrust.

And one of the biggest elephants in the room is the fact that we already produce enough food to feed 10 billion people (the global population as of this writing is approximately 7.8 billion), yet we still waste 40% of our food supply.

More grass-finished, regeneratively-raised beef not only means healthier land but also healthier local economies and more profitable ranchers - specific numbers we can dive into at another time.

More regenerative agriculture also means healthier people, communities, soil, water cycles, mineral cycles, and biodiversity.

In these conversations, it’s also important to remember that it is not the job of our local farmers and ranchers to “feed the world.” They feed their local communities. Every country has the right to produce food for its citizens that’s environmentally, culturally, and biologically appropriate.

When we rely on food we can produce sustainably ourselves instead of relying on outside food, we are more resilient.

The goal should be to help local food producers learn to care for their land in a way that not only results in the healthiest food but also the healthiest ecosystems.

An increased reliance on industrially produced grains (looking at you, fake meat products) is not the answer to a scaleable, healthy, sustainable, and just food system.

We can produce more nutrient-dense food in a way that benefits our health, our economies, and our planet.

What do you think? How would you propose we shift our entire beef supply to regenerative?

Additional reading:

Using soil type to estimate potential forage productivity

Scaling Grass-fed Beef by Allen Williams

Regenerative agriculture for food and climate

The role of ruminants in reducing agriculture’s carbon footprint in North America

Weird things cattle eat and it is perfectly OK

Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate

We Already Grow Enough Food for 10 Billion People … and Still Can't End Hunger

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features - we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.

If you have any products you would like to see featured, please respond to this newsletter or send an email to meg(at)soil.works

The Regeneration is brought to you by Wholesome Meats | Soilworks | Grassroots Carbon| Grazing Lands

Those that claim that grazing animals can only make a marginal contribution to human nutrition are mistaken.

Those that claim that we can feed the global population with grass-fed beef are equally wrong. Even with (heroic) assumptions of double productivity with improved grazing methods, such as AMP or holistic grazing, we are very far from “feeding the world”. However, such improvements would make it possible to produce beef and milk on current consumption levels from grasslands only.

https://gardenearth.blogspot.com/2021/05/we-cant-all-live-on-grass-fed-beef-but.html

Another thing is that we need to look at this more globally. Especially in former Soviet republics, like Kazakhstan, there are vast areas of steppe-like vegetation just waiting to be grazed Holistically. The Netherlands, with its delta-landscape is more suitable for crop production. Etcetera. The last IPCC report explicitly mentions this: grow the type of food where the conditions are most suitable for that type of food.