🌊Turning the Tide of Our Water Crises with Regenerative Agriculture

Science: Industrial agriculture is the leading water pollutant on the planet. The world is facing a water crisis that has affected the water supply quantity, quality, and the health of ecosystems reliant on water. Be it from excess fertilizer application and nutrient contamination from industrial crop production or lagoons of manure from concentrated animal feeding operations(CAFOs), the damages towards our freshwater ecosystems are well documented - even 77% of companies mentioned water as a risk factor in their financial filings. Two key claims must be recognized to begin addressing the issue:

Our water quality is universally affected by agricultural runoff(“nonpoint source pollution”).

According to the USGS, “about a half million tons of pesticides, 12 million tons of nitrogen, and 4 million tons of phosphorus fertilizer are applied annually to crops in the continental United States.” This had led to at least one pesticide being found in over 94% of water samples, 90% of fish samples from streams, and 60% of shallow wells from around the US. Essentially, due to tile drainage pipes used on 46% of farm fields, fertilizer runoff can enter waterways easily once soils are saturated. This has led to large fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay, along with a “dead zone” spanning thousands of kilometers from the Mississippi River into the Gulf of Mexico. Even algal blooms have affected coastal communities in Florida, leading Miami to ban glyphosate use. Farmworkers are particularly exposed - we must not forget the human cost of this water pollution.

“Blue water” sources of freshwater are being depleted without regeneration and water pumped into agricultural systems is threatened by extreme weather conditions.

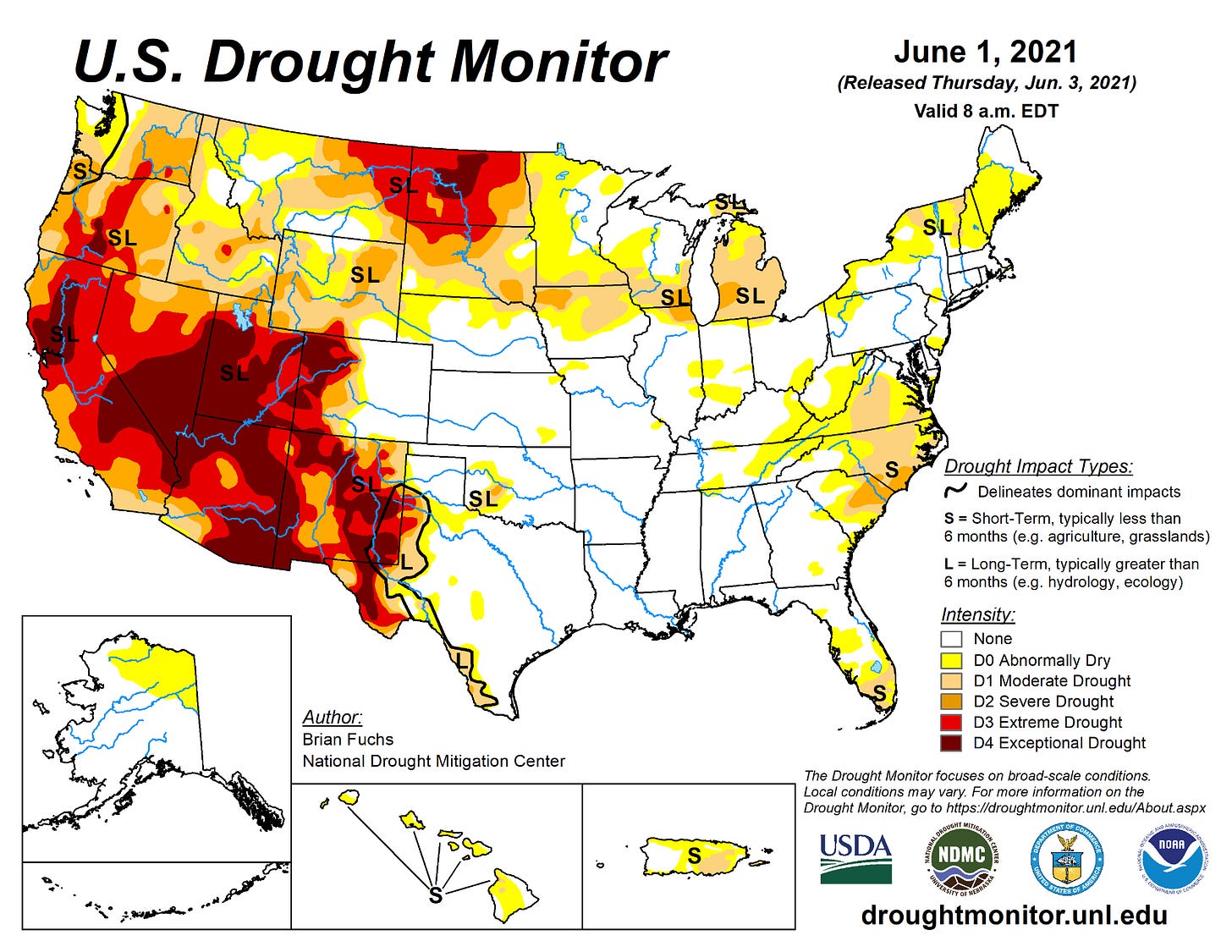

Though a lot of water used in our food system comes from rainfall (“green water”), about 20% is stored in rivers, reservoirs, or aquifers (“blue water”). Blue water is particularly delicate because it can take centuries to replenish, especially in areas of drought and arid climates. The Ogallala Aquifer, for example, would take 6,000 years to refill and is still being drawn out unsustainably. As 97% of the Western United States faces “abnormally dry conditions”, reliance on blue water only further increases, leading to a vicious cycle.

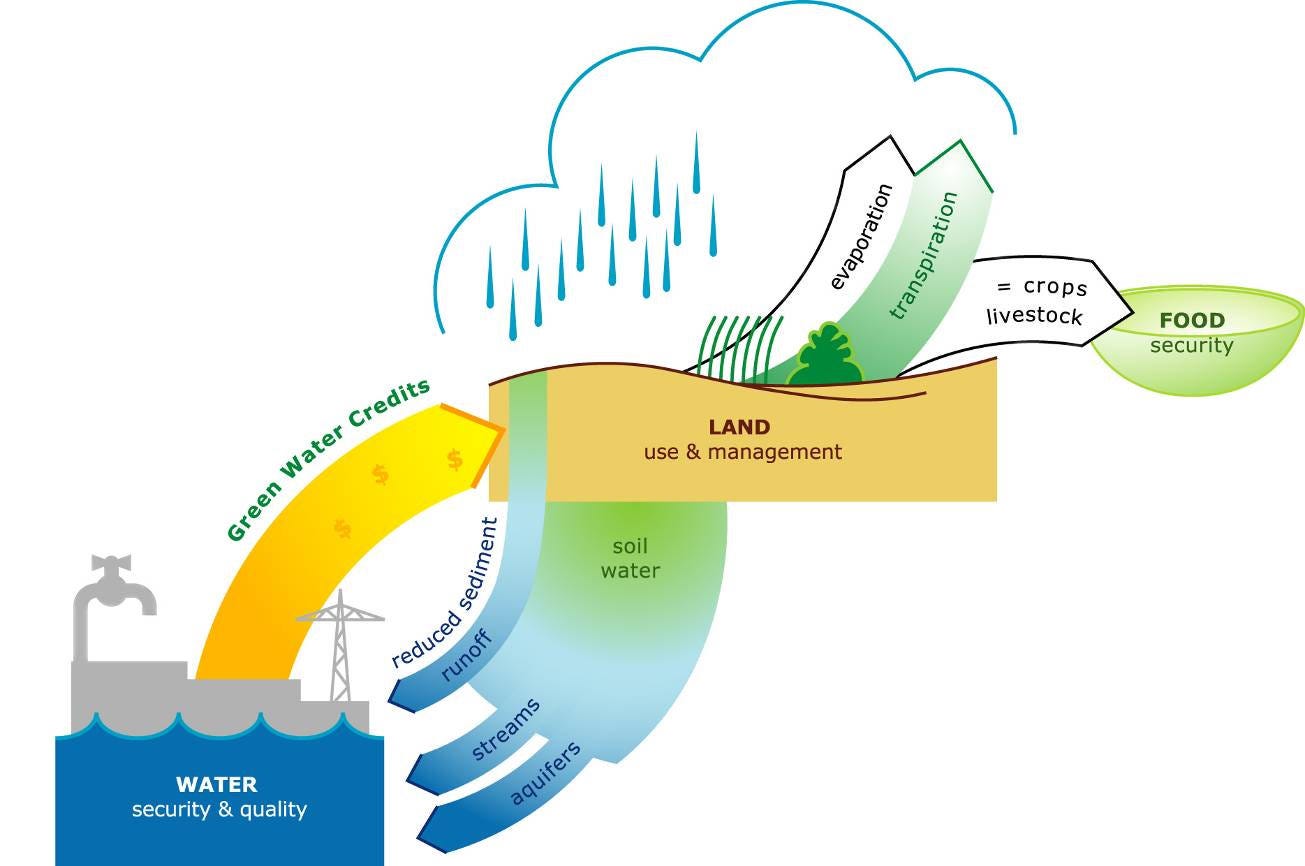

It’s important to understand how the mechanics of the water cycle have been disrupted by farming practices - and how regenerative agriculture can help adjust it. The “soil carbon sponge” that we touched on last week can fix the water cycle. Bare soil, uncovered and unprotected by vegetation, cannot effectively absorb rainfall to recharge underground water pools (like aquifers). Here’s the rub with land management: bare soil is not necessarily caused by a lack of rain/drought, but rather poor land management causes bare soil and its subsequent negative effects that are compounding over time. Indeed, even water vapor that evaporates from bare soil and mixes with dust from desertified fields can turn into a haze that is a greenhouse gas.

However, the focus on land management should be a cause of optimism: the right practices and approaches can lead to more water infiltration, leading to greater transpiration and global cooling. As regenerative rancher Gabe Brown testified before Congress, his farmer has been able to increase his soil organic matter percentage by over 4% and with it, his soil water infiltration by over 16x. An increase of 1% in soil carbon should correlate with a capacity to hold water by 170,000 liters per hectare, which means that 17 mm of rain can be held in the rain per 1% increase of soil carbon. In particular, cover cropping and pasture cropping provide cover to soils and allow for managed systems like Mr. Brown’s. This can reduce nitrogen runoff, though nitrogen oxide emissions can linger even after the implementation of these practices. Combine that with the use of livestock integration and biofertilizers in lieu of synthetic fertilizers and the process can be rapidly sped up. The implementation of conservation practices has begun to replenish depleted aquifers.

The key issue I see here is finding ways to measure and incentivize these changes within the agricultural system. Three levers exist:

Experimenting with “water credit” marketplaces a la carbon credits: The creation of “green water credits”(GWCs) and “nutrient markets” are focused on incentivizing payments for the outcomes of more water infiltrated into the soil and avoided nutrient runoff, respectively. GWCs have been piloted internationally, and in the states, various new marketplaces targeting carbon credits are “stacking” water on top. For example, the Soil and Water Outcomes Fund provides financial incentives to farmers and ranchers who improve their water infiltration rates, while the Ecosystem Services Marketplace Consortium is providing foundational literature on measuring and commoditizing both water quantity and quality as ecosystem services. The EPA is in favor of water quality trading markets, as “nutrient” markets can be found in various states (click through to see a great map), of note being those states around the Chesapeake Bay.

Direct policy interventions: In an attempt to stop the bleeding of aquifers, California and other states are paying farmers to stop working fields and cut their groundwater pumping. Though this should only be a measure of last resort, as the incentivization of land management that stores and replenishes aquifers is the only path forward, it will be a tempting option for policymakers to show action at a fraction of the cost. The EPA also has broad, legislation-backed powers, particularly with CAFOs. However, deregulation and guidance have led to a lack of enforcement. One area to watch is the regulation of countries and corporations using “the virtual water” on American farmland for unsustainable farming practices and then exporting the raw goods internationally while depleting water resources (much is still unknown here).

Innovative technologies: Though not a “new” technology, better irrigation and the rise of regenerative aquaculture are welcome developments for optimizing water usage and helping restore damaged ecosystems. For example, The Nature Conservancy has oyster restoration programs throughout the Chesapeake Bay, Gulf of Mexico, and other regions. Oysters can filter as much as 50 gallons of water a day of toxic pollutants and nutrients. On the other hand, startups like n-drip provide scalable irrigation infrastructure beyond traditional “flood” irrigation. Measurement and monitoring for water quality and quantity are also improving through the proliferation of hyperspectral imagery to monitor water quality.

“Regenerative hydrology”, be it in agriculture or other complex designed systems, consists of four key “r” components: receive, recharge, retain, release. First, you must slow down the reception of water so that it does not run off and then is infiltrated. Then, the water must be spread out - particularly downwards in aquifers or, for example, bison wallows that stimulate biodiversity. Water should naturally sink into the soil through plant and tree roots and “recharge” both vegetation and the bodies of freshwater we rely on. Last, water should be naturally released into bodies with minimal if any pollution and evaporated into the atmosphere.

Implementing such a framework should be a feasible step forward. However, measuring outcome changes and creating compensation mechanisms for those ecosystem services are important, as aquifers are public goods. The water-related benefits of regenerative agriculture deserve more attention and measurement, reporting, and monitoring on it at scale will be crucial moving forward.

Shop: Our friends at Wholesome Meats were recently featured in a Spectrum News story that was shared across all of their channels nationwide. The story details how their founder, Lew Moorman, ventured from the tech industry to regenerative agriculture and serves a cri de coeur for folks hoping to enter the space. Take advantage of their 15% off deal right now with promo code SIMMER15 (Discount valid until 10/18)!

Read: Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Professor Robin Wall Kimmerer is an important book that contextualized my understanding of “regenerative agriculture” within a larger indigenous tradition of botany and stewardship. I am still stewing on it, but I’ll leave you all with a quotation from her book: “Action on behalf of life transforms. Because the relationship between self and the world is reciprocal, it is not a question of first getting enlightened or saved and then acting. As we work to heal the earth, the earth heals us.”

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features - we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.

If you have any products you would like to see featured, please respond to this newsletter or send an email to Kevin(at)soilworksnaturalcapital.com

The Regeneration is brought to you by Wholesome Meats | Soilworks | Grassroots Carbon| Grazing Lands