What gets measured, gets…manipulated.

The impossible business of quantifying a planet resistant to quantification.

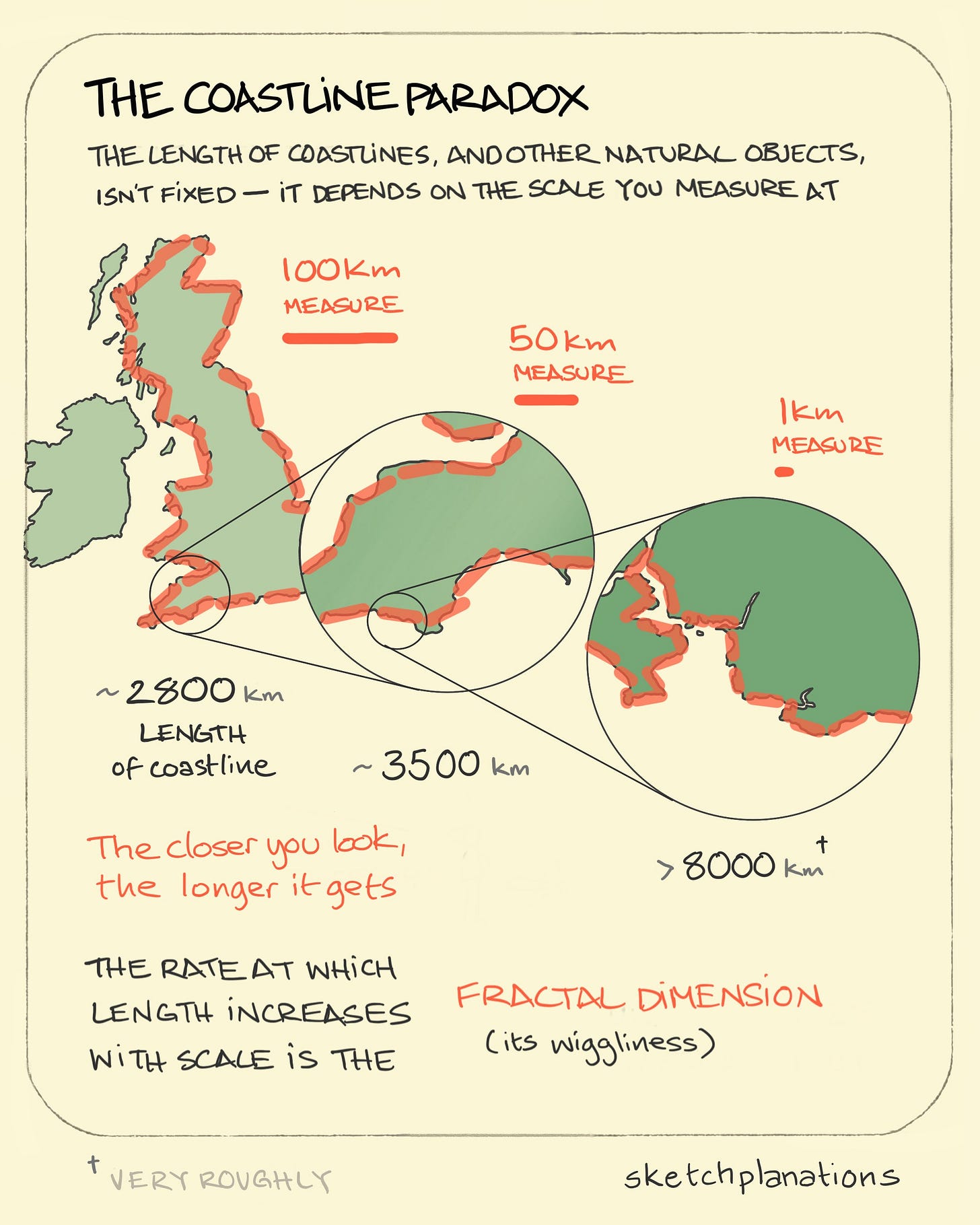

It’s impossible to measure coastlines and borders. In a phenomenon dubbed the “coastline paradox,” the measured length of coastlines and other natural objects depend on the level of detail or scale at which it was observed.

If I measure a coastline or a border from a satellite, for example, I’d get a vastly different number than if I were to pace around the edge on foot. As shown in the above video, halving the ruler increases the length of Great Britain’s coastline. In other words, the smaller the ruler, the longer the length.

The coastline paradox was first discovered in the 1950s by mathematician, Lewis Fry Richardson, while trying to predict the likelihood of war between two countries based on the length and nature of their common border.

To test his theory, he examined different borders in Europe and discovered peculiar disagreements. The Portuguese claimed their border with Spain measured 1,214 km, whereas the Spaniards believed it was only 987 km. Similarly, the reported length of the border between the Netherlands and Belgium varied between 380 km and 449 km.

This trend of discrepancies, or “fractals,” extends to the behavior of many other natural phenomena and doesn’t even consider that Earth is in constant flux, always transforming itself anew.

Math, and our efforts to quantify and simplify everything, are dull tools to wield in an attempt to understand this complex planet.

“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.” – John Muir

For example, methane. It’s the boogieman of greenhouse gases, claimed to be worse than carbon dioxide due to its comparative global warming potential. When many climate-concerned people hear this, they broadly swath methane, and anything that produces it, as planet-enemy number one.

They subsequently learn that cattle produce methane during enteric fermentation, the process of microbial fermentation in the digestive system of ruminant animals, where microorganisms break down complex carbohydrates into simpler compounds, such as volatile fatty acids and gases like methane.

This gas in the form of cow “burps” is increasingly the subject of attention for climate activists. Methane has become the number one argument in recent calls to end all livestock farming in favor of “rewilding” landscapes to restore populations of wild animals.

On the surface, it seems to make sense - who doesn’t want fewer boogiemen and more wild animals in the world?

But if we’re using methane emissions as our ruler for a “healthy planet,” then we’ll still be at war with a “rewilded” world because methane emissions would not necessarily decrease.1

The animals that would replace cattle (e.g. deer, moose, elk, wildebeest, giraffes, etc.) are also methane-producing ruminant animals.

So, we find ourselves in yet another paradox, letting a math equation decide what metrics matter and whether or not a species that have roamed the planet for millions of years should live or die.

This is further exacerbated when we look at the Sudd Wetland in South Sudan.

The South Sudanese wetland is one of the largest freshwater ecosystems in the world, covering about 22,000 square miles. In 2019, however, Yale360 reported that “researchers estimate that wetlands in Africa’s tropics could account for up to a third of the spike in global methane emissions between 2010 and 2016, with most of this coming from the Sudd.”

If we’re still using methane as our ruler, we should eliminate this methane source, too, right?

“The Sudd is home to thousands of crocodiles, hippos, elephants, and zebras, as well as the majority of the world’s shoebill storks. It also sustains one of the world’s largest mammal migrations, in which around 1.3 million antelope — comprising white-eared kob, tiang, and Mongalla gazelle — move each year from the Sudd east across hundreds of miles of open grasslands to Gambella in Ethiopia.”

Advocating for ecocide in order to reduce one metric - methane - is myopic and dangerous.

Fixating on only the easily quantifiable at the expense of a planet full of things that are inherently resistant to reductionistic measurements is the same industrialized, monoculture thinking that got us into this climate crisis in the first place.

Our obsession with numbers, oversimplification, and objectification of nature treats the world as if it “were a giant spreadsheet which only needs to be balanced correctly”2 so we can go about business-as-usual without the methane or carbon.

Or worse.

These calls to be obsessed with quantification and technocratic “solutioneering” disconnect us from life itself, disenfranchise us from a life within ecology rather than further away from us, and leave us as nothing more than servants of debt and cogs in a machine of promissory innovation. We’ll lose access to one of the most nutrient-dense foods we can eat and directly and indirectly condone the bullying of those who both feed us and steward this planet we call home.

As Paul Kingsnorth notes:

“If you can’t read or understand the ‘peer-reviewed science’ then you are open to being intimidated into fearful silence by those who can, or claim they can. And those people - drawn, as all green ‘thought leaders’ are, from the upper strata of society - will bring with them a worldview which treats the mass of humanity like so many cattle to be herded into the sustainable, zero-carbon pen.”

Because we tend to view our world through the scientific method alone doesn’t mean that relationships between things are nonexistent, that our world can be understood in a vacuum, and that we can eliminate methane-emitting cattle that are critical to some of the most biodiverse ecosystems on the planet.

We can continue to advance science; we can continue measuring things, but we have to acknowledge how our “datafication” can reduce our worldview. These tools and metrics represent one part of our story, not the story.

While we can’t “peer-review” our intuition and sense of belonging to the world, we also can’t continue to use our addiction to facts and figures and numbers as a shield from our discomfort with complexity, uncertainty, and worst of all, complicity.

Livestock can go beyond methane and help regenerate livelihoods, local economies, and restore and maintain optimal health, biodiversity, and carbon sequestration of our agro-ecosystems.

We can amplify these nature-based solutions that benefit our planet beyond carbon and recouple humans into ecosystems as stewards.

And instead of spending our lives measuring coastlines only to realize it’s impossible, we can dig our toes into them - feel them - and embrace the complexity of this planet we call home.

Disclaimer: The Regeneration Weekly receives no compensation or kickbacks for brand features - we are simply showcasing great new regenerative products.

If you have any products you would like to see featured, please respond to this newsletter or send an email to meg(at)soil.works

The Regeneration is brought to you by Grassroots Carbon, a regenerative carbon credit provider incentivizing grassland regeneration at scale. Are you a rancher interested in being paid to sequester carbon? Learn more here. Are you interested in buying carbon credits that support regeneration and impacts beyond carbon? Learn more here.

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-023-00349-8

https://dark-mountain.net/the-quants-and-the-poets/

I want to say "Who are you?" Without question, you are the best writer and essayist on regeneration.

Thank you for so well expressing what our intuition tells us is causing harm. And for the term 'technocratic “solutioneering" '.